puzzles

and the pursuit of play

Art and creation are wholly intertwined concepts. The pursuit of novel and inventive thought comes bundled with the assumption that something new must be made; the existence of the word creativity itself evokes the persona of the 14th-century artist-inventor buried in its etymology.

Not all creation is art, though. The typical Lego set gives you pre-portioned pieces and a detailed manual which leaves no room for interpretation. Even though millions of people have built exactly the same thing, and very little creativity (in the traditional sense) is involved, nobody would contest the fact that you’d have created something by constructing a set.

In childhood, creating for the sake of creation is as natural and plentiful as breathing. I’d invent new games, or build elaborate wooden-block cities, or mash all my Lego sets together in Avengers-like fashion only to clean it all up and completely forget about it the next day, ready for the next adventure.

My inner child still longs for play. There’s something sacred about self-contained effort; to think and do things without a need for reason or external validation.

It’s curious how the word puzzle is nearly synonymous with jigsaws, and yet unlike nearly any other type of puzzle, they aren’t at all an advanced challenge of intellectual thought and abstract reasoning.

I’ve been building jigsaw puzzles for as long as I can remember; very little has changed in the methods or strategies I use to build puzzles since I was barely old enough to clear the choking hazard age on the box.

There are people out there who are very, very good at puzzles. (Take a look at Kristin Thuv winning the 2024 Jigsaw Puzzle Championship just last week by building a 500-piece puzzle in 38 minutes!) But even the competitive puzzling scene doesn’t have any advanced theory, strict training regiments, or standard technique— the only consensus for improving is to practice. A lot.

Ignoring corners and edges, the total number of ways to arrange n standard jigsaw puzzle pieces is

For any respectably-sized puzzle, this number is so large we cannot even begin to comprehend it. For example, a 500-piece puzzle would have approximately this number of arrangements:

130,738,711,099,440,736,186,561,741,551,555,000,605,088,328,452,285,958,608,949,739,490,558,485,988,053,943,126,073,919,411,802,268,453,002,994,430,167,086,682,966,046,060,428,801,634,700,773,410,669,230,750,893,224,158,624,161,827,067,202,644,022,409,000,837,615,123,671,689,682,467,262,502,376,700,727,476,698,405,749,361,814,310,214,869,251,942,773,416,205,369,556,142,966,264,511,378,880,672,388,604,302,839,742,619,550,409,463,172,594,434,363,563,368,852,212,387,534,755,509,913,805,712,094,224,762,605,812,866,923,450,557,538,857,959,515,969,249,516,733,627,021,317,718,336,497,689,759,165,021,938,448,507,176,930,141,322,574,842,943,317,234,561,539,979,385,726,580,828,274,672,394,717,048,234,238,222,483,711,192,115,174,838,634,787,273,502,550,962,501,060,552,716,347,158,476,485,211,378,890,426,540,340,248,757,871,804,649,404,316,482,160,377,234,633,868,473,419,458,373,488,873,274,529,550,753,370,917,639,646,023,781,011,034,579,245,735,342,309,141,267,136,521,469,300,687,371,727,687,907,923,859,751,249,306,733,556,871,149,163,772,973,342,157,921,187,522,508,876,109,145,473,165,250,659,357,581,908,563,190,241,192,072,131,905,983,440,572,979,937,589,911,567,787,405,915,418,456,606,919,817,360,557,418,525,360,168,020,755,621,336,556,428,927,639,210,038,755,950,769,865,333,468,157,742,300,792,736,100,828,125,809,743,678,276,153,078,572,373,190,601,745,449,693,860,282,532,332,792,503,659,856,639,231,723,253,658,383,596,426,598,320,088,850,237,645,396,268,497,918,442,487,555,487,340,926,859,523,969,761,169,028,689,965,311,028,749,744,547,602,667,816,745,324,976,062,231,197,150,205,120,399,345,957,816,113,940,057,755,972,212,064,653,510,844,044,101,261,908,526,975,161,198,726,401,228,800How is it even possible for a human to build a 500-piece puzzle, let alone in less than an hour? We can get a few clues from attempts to engineer puzzle-building robots12, but they can only go so far in modeling real human ingenuity.

actually building a puzzle

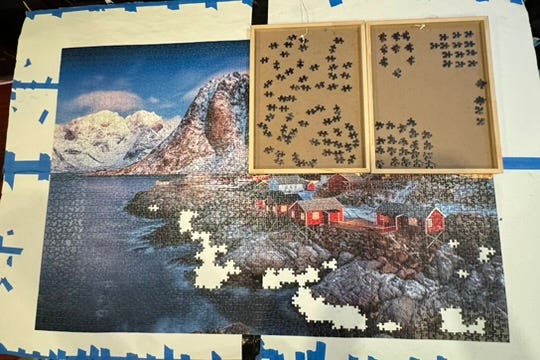

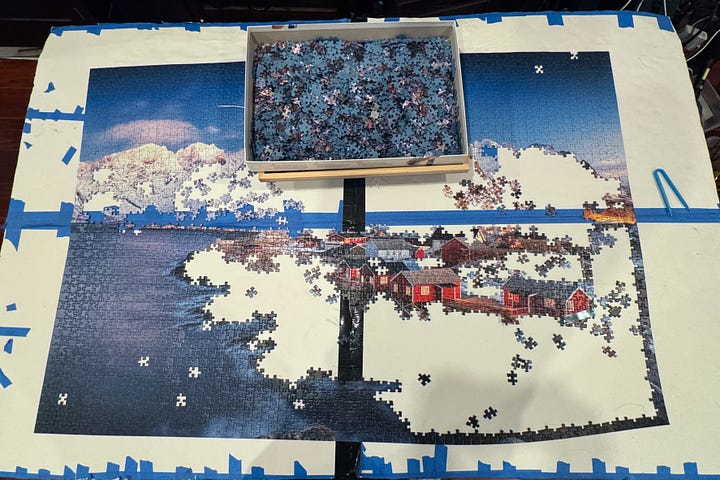

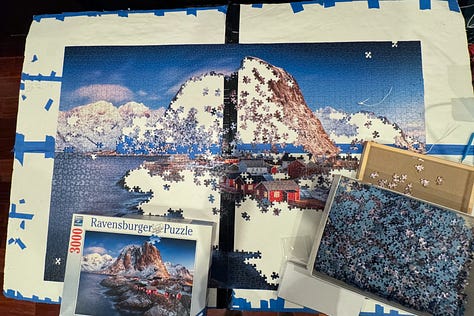

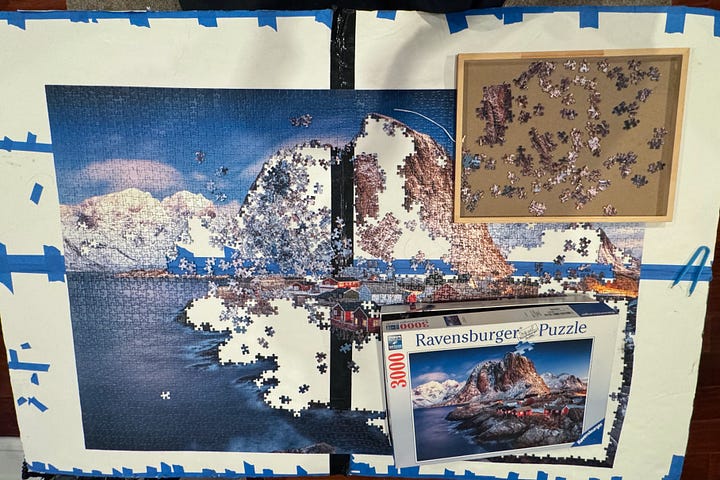

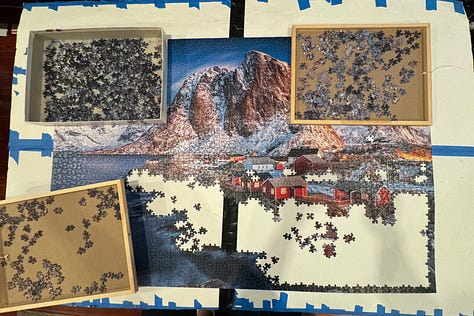

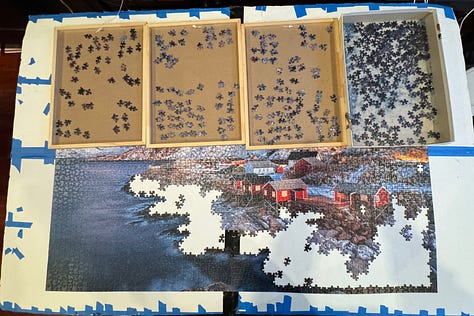

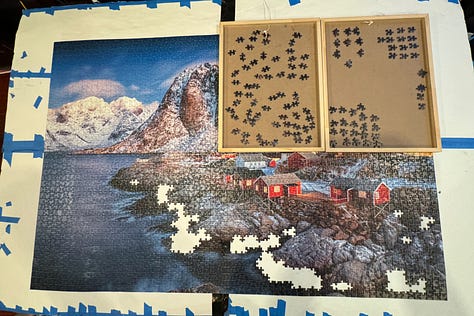

In an attempt to understand the how and why of puzzle-building, I’d like to walk through the process behind my most recent build.

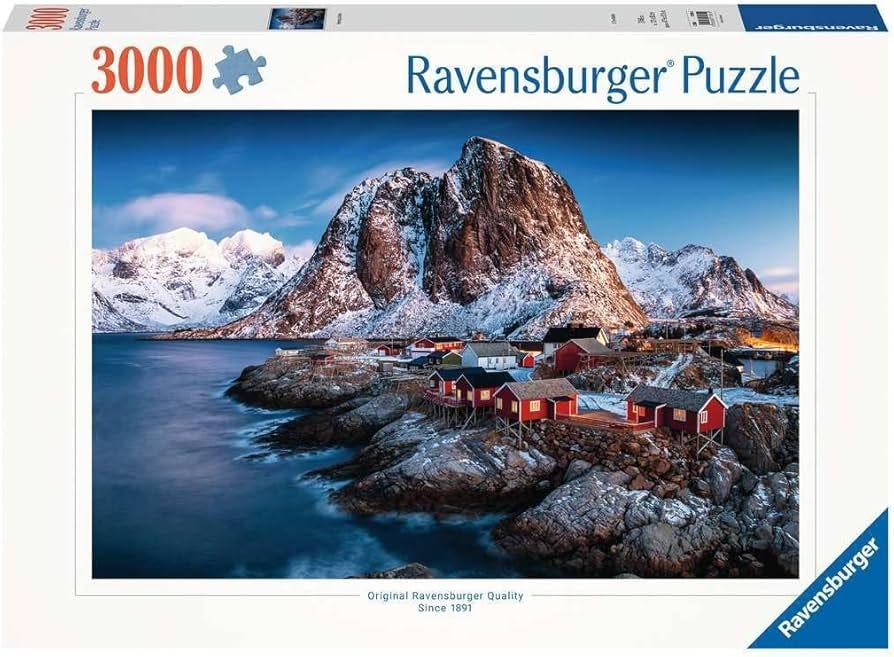

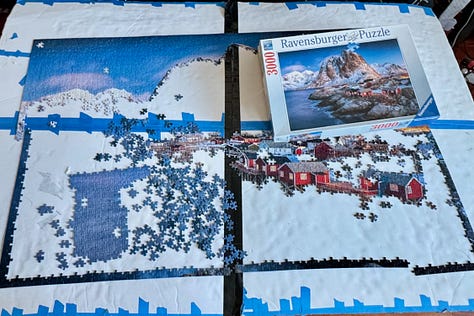

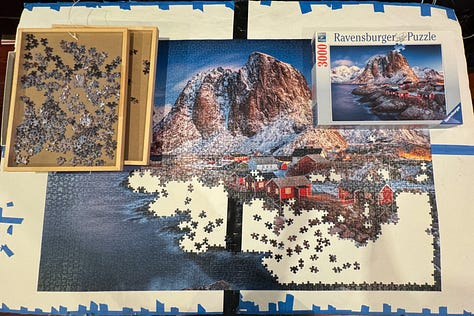

Looking for a challenge, I’d picked up this 3000-piece Ravensburger puzzle depicting the Norwegian village of Hamnøy.

I’ve never keep track of time while building before, and I was curious to know how long it’d actually take. So over the span of the six real-life months it took to complete, I’d set a timer for 1-hour chunks, build nonstop until it went off, then take a picture at the end.

Being nearly 4 feet wide, this puzzle took up a decent chunk of the living room. Visitors would often try to get a piece or two in, but few were successful: besides the obvious features of the houses, there’s very little to grasp at for someone who hadn’t been staring at this picture for tens of hours. If you’re looking for a coffee table centerpiece, this ain’t it :p

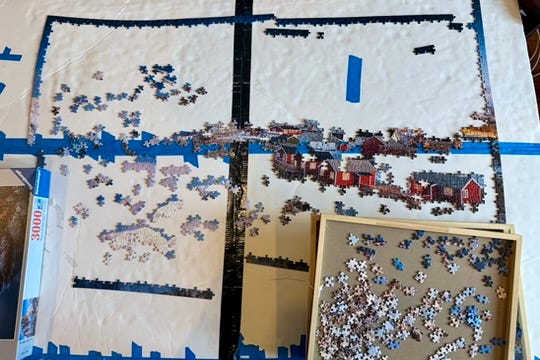

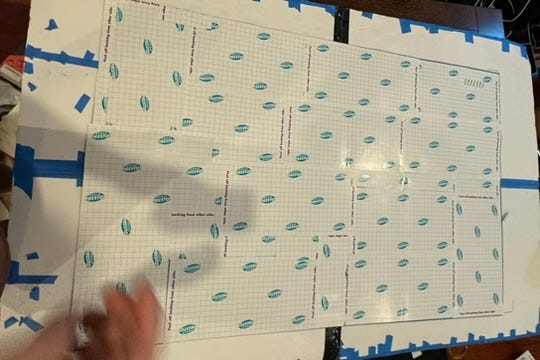

In order to have a large-enough portable surface, I taped four of these 18-by-24-inch foam boards together. I also have one of these wooden puzzle boards which usually works well (and has neat drawers!), but it’s only large enough for 2000-piece puzzles.

hour 1

According to speed-puzzlers, there’s no time-saving advantage to building the edges first, and many avoid it.

I always kick off builds with it, though. It makes the process of sorting through the massive pile of loose pieces much less daunting, and literally gives a frame of reference for what’s to come.

At the same time of digging for the edges, I tried decluttering the pile by separating all of the plain-blue pieces I came across. The fact that the backs of the pieces are blue didn’t make it any easier 🙃 (I also had no idea which of them were sky vs. ocean pieces, but I didn’t care for the time being.)

Having spent most of the hour sorting rather than building, I didn’t have much to show- but it’ll go faster soon!

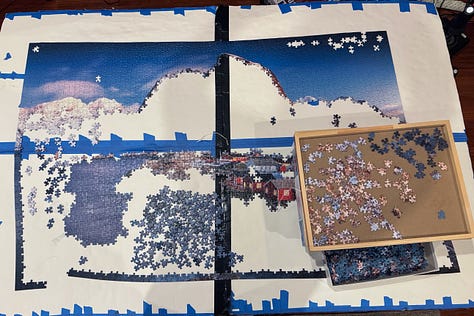

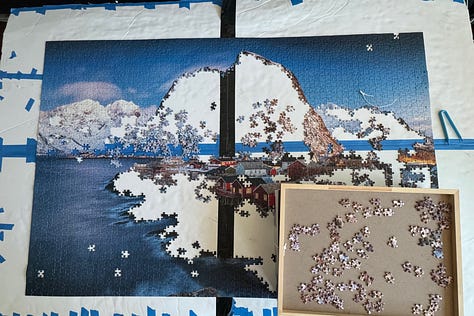

hour 2

The frame’s looking a lot nicer now, but there’s still a lot more to do before it’s complete!

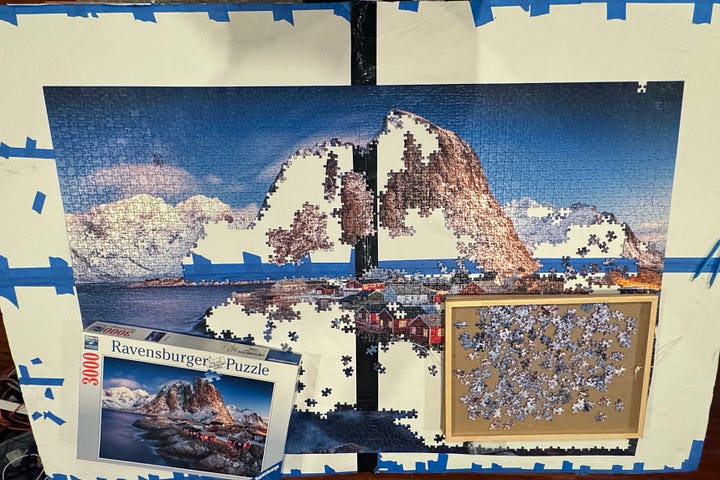

There’s a very clear threshold of diminishing returns for continuing to build out the edges, unless I went through and sorted every single piece first (which, again, is something speed-puzzlers do but I don’t!). A heuristic I personally follow is that if I continuously search through all of the pieces for 2 minutes and can’t find any edges, I should move on to the next phase. The rest of the edges will slowly emerge anyways as I search for non-edges!

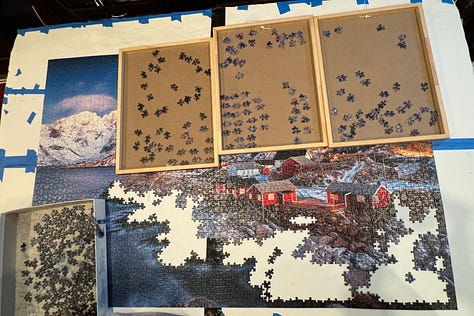

Right after that condition is met, I usually try going for what looks to be the easiest, most identifiable section of the puzzle to do next. In this case, it was the smattering of red-and-white houses along the coastline.

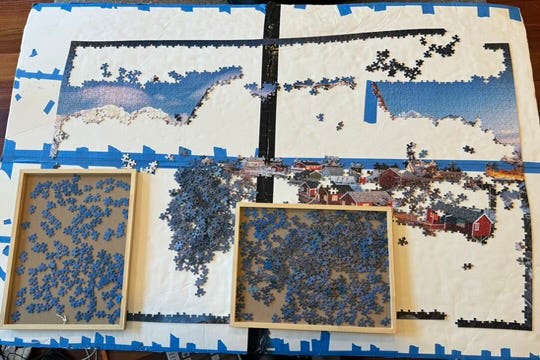

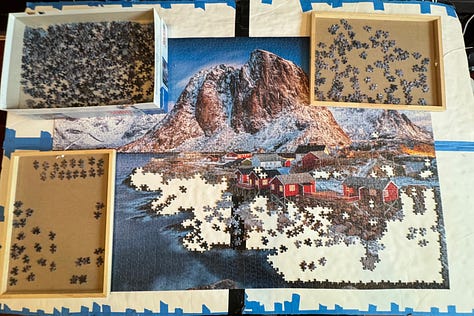

hour 3

When the luxury of identifiable patterns presents itself, I’ll happily take it! This is perhaps the only point in this puzzle where I can look at a red piece and say “yes, this is definitely the door of the 3rd house to the right”.

In this sense, the houses are a very well-defined subpuzzle: if a piece is red or roof-textured, there’s a 100% chance it belongs here.

Hole-patching (where there’s a missing piece somewhere, and you’re trying to find the exact fit) only works in cases like these where there are only a few possible pieces, and all of them have distinct patterns. But when it’s available, it’s usually the fastest way to make progress!

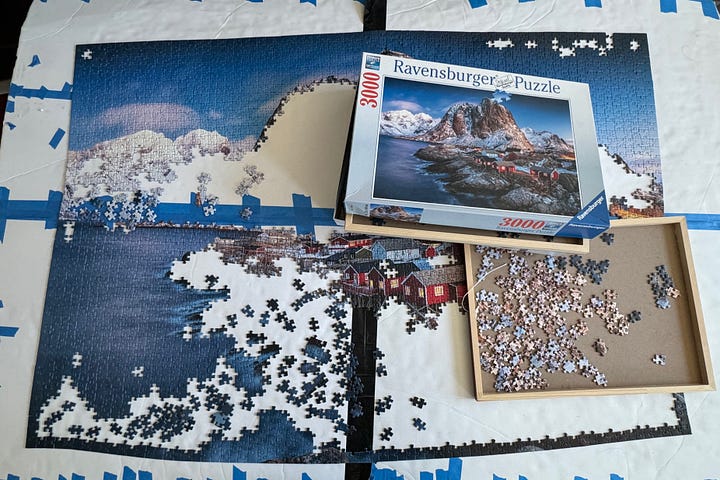

hour 4

Having exhausted all the obvious house pieces, I turn to the second-most recognizable group of pieces: the border between land and sky. These types of boundaries are often very distinct, and made even more so this time by the pure-white snow of the mountains.

Hole-patching won’t work anymore: any one pure-white pieces could really go anywhere on the mountain, and any one border piece could be at any position on the boundary. (The question of maybe becomes dangerous in puzzle-building. If you have 100 pieces that could maybe fit somewhere, you’d need to, on average, try 50 of them to find the right one.)

The next strategy to move onto is similarity: given a large group of similar-looking pieces (like the sky!), pieces that are more alike are more likely to be close to each other.

hour 5

It turns out that the beginnings of the sky were quite nice! The left side had a super distinct cloud, and the right side featured an unmistakably light shade of blue.

I thought there’d be a huge issue sorting sea-blue from sky-blue, but it doesn’t seem like it’s come into play (yet… dun dun dun)

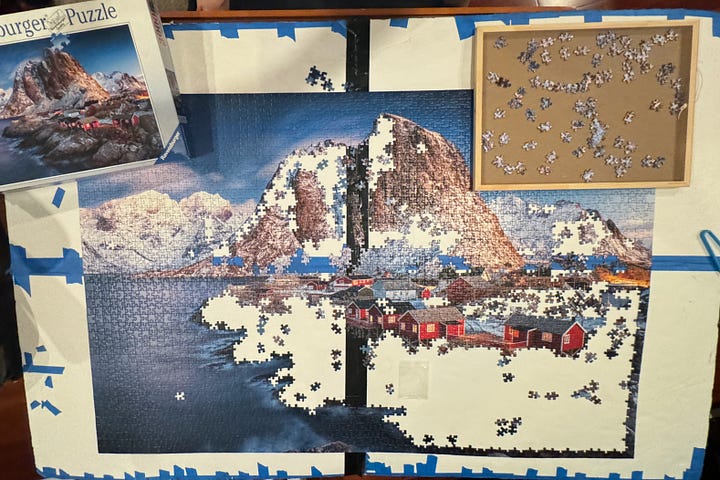

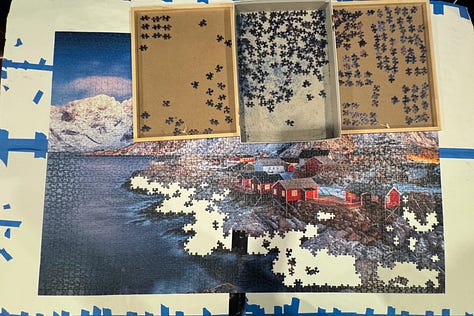

hour 6

One surprising experience I’ve had with puzzles is that the plain gradients, like the sky, are among the easiest components to piece together.

This is probably because they’re a pure application of the similarity heuristic: there’s absolutely no chance that two pieces of the same shade will be unexpectedly far from one another. (They could still be on opposite sides of the puzzle, in the case of the sky— but still on the same layer!)

Given this property, the right side of the sky is coming along smoothly. All I need to do is find the lightest-blue pieces remaining, take them out of my pile of blue pieces, and repeat as the sky grows upwards.

hour 7

This picture is a little scuffed. I don’t know what that black thing is, either…

Anyways, the sky has crept up a couple more layers. Yay :))

So far I’ve addressed a bit of the how question; I’d like to give some attention to why: why subject myself to the tediousness of staring at nearly a thousand pieces of varying shades of blue? Why spend indeterminate amounts of time constructing an image instead of just buying an identical poster on Amazon?

For me, part of it is in how effectively it can fill up the part of my brain that’s itching to do something, no matter how much that is—

getting lost in thought about something I need to ponder;

idly trying every combination of pieces while on a long phone call;

falling into a flow state and completely losing track of time while speeding through big features

In this way, I see puzzles as physical manifestations of listening to music. (I’d also often listen to music while building too, which is an interesting cognitive interaction to ponder!)

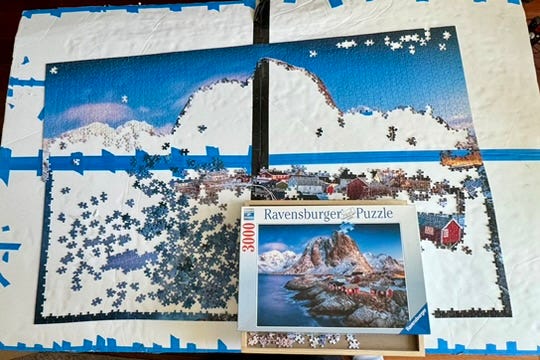

hour 8-10

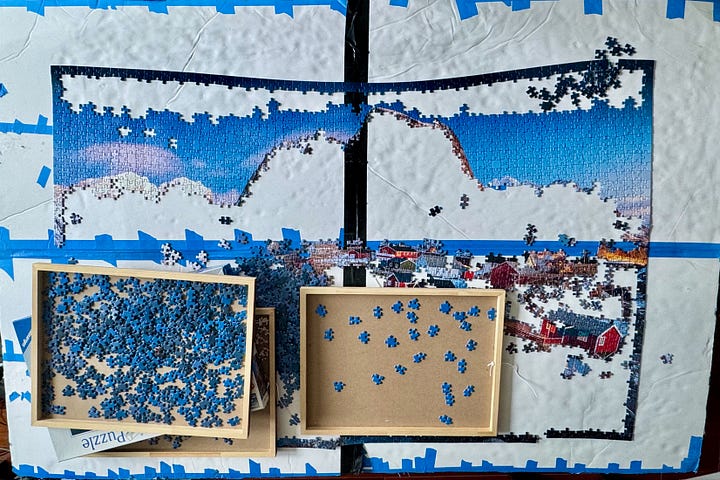

After ten in-puzzle hours: I’ve finally fit every piece of the sky I know to exist. (There’s quite a few remaining a the top right, but my perception isn’t yet trained enough to distinguish them from the ocean.)

In these ten hours, three months have passed IRL. I don’t like leaving things unfinished, so this was a test of patience and active prioritization. Finding a day in which building a puzzle is the most pressing issue is incredibly rare, but so nice.

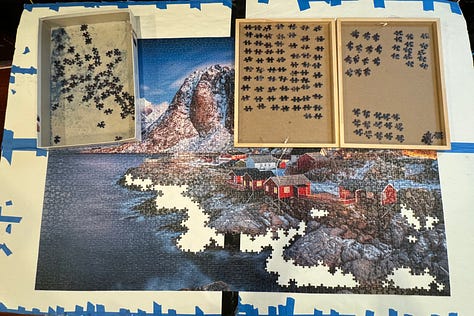

hours 11-17

Ocean time!!

The process of building the ocean was nearly identical to the sky, so I won’t introspect on it too much.

Notably though, it was a significant difficulty jump— mostly because the gradient was much more poorly defined. On the middle fringes, the pieces could have gone anywhere surrounding the bright reflection; and at the very edges, the dark blue-grays blended into the mossy outlines of the rocky coast.

Like musical pitch, I think there’s an acquired skill of being able to tell apart relative shades of color.3 The ability to consistently decide if one shade of blue is slightly lighter or slightly darker than another shade of blue often is all that separates 1 hour vs. 10 hours of trial and error. (Lighting matters a lot here, too— this section was a couple orders of difficulty easier during the daytime!)

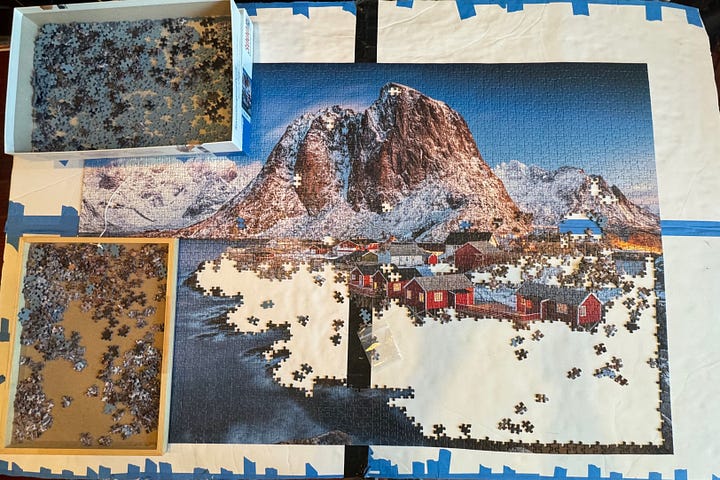

hours 18-24

The big mountain at the heart of this puzzle is an interesting case: while seemingly gradient-like, the gradient fluctuates so wildly as to be more distracting than helpful. But after a few rounds of taking way too much time figuring out where an obvious-looking piece should go, I slowly built up a mental model of how the different shades of rock and snow intertwined. Whereas the darkest shades seemed to be the crux of this section in the beginning, I found out that they came together surprisingly quickly.

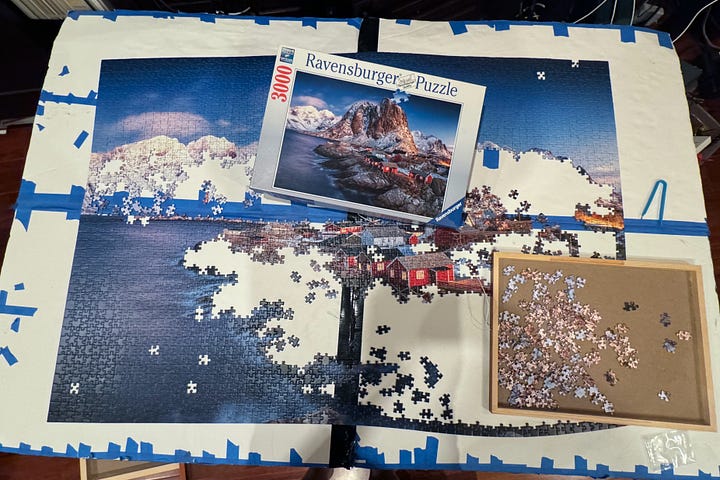

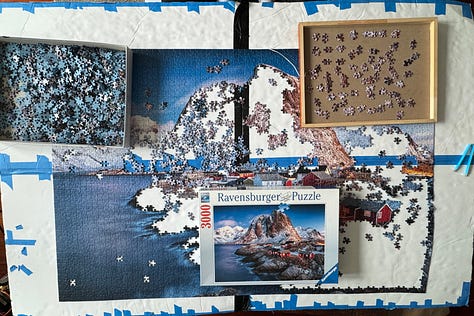

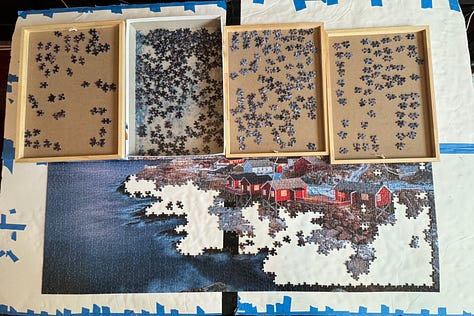

hours 24-33

As with most things in life, I am very bad at estimating how long a task will take.

Moving to the last section, I was confident I’d be able to pull through in a few hours— after all, there were only a couple hundred pieces left!

But 2 hours turned into 4, which turned into 6 then 9 over the course of a week of trying to get the last pieces in.

I guess I shouldn’t be that surprised, as the final section of rocky terrain was by far the most difficult one on this puzzle. Most of the 200-odd pieces look completely identical, so I had to fall back to solely relying on matching shapes (like an all-white puzzle…)

This is hard, but not as hard as it might sound. The standard 4-sided jigsaw puzzle piece has a few distinct possible shapes:

The first three pieces are somewhat uncommon.

The 4th and 6th pieces (all nubs or all holes) are fairly rare, and the most challenging to fit.

The 5th piece (2 nubs and 2 holes across from each other) is by far the most common piece.

So the general idea is to identify the slots that can cannot fit the common piece, and try to fill those first— this cuts the possible number of candidates by about half.

Then, certain features of the shapes help narrow them down further: maybe a slot has an unusually large hole, or has a nub that’s super far to the right, or has an aggressive curve. While it still takes some trial and error, the easiest slot on the board should rarely have more than 10-20 viable candidates. And trying 20 pieces is way more manageable than trying 200!

Here is the nearly-final state of the puzzle, with just short of a hundred (nicely sorted) pieces to go:

finale

At last: I have a shiny new thing to hang up on the wall :)

If you’re curious about how all the pieces are staying together— I like to buy a bunch of these puzzle stickers and stick them onto the back:

Flipping the puzzle is really scary, but overall I think it’s a much cleaner and longer-lasting way to preserve puzzles compared to the glue that most people use. Maybe it’s a skill issue on my part, but I’ve found the glue to be really hard to spread evenly, and then it gets everywhere, and then the puzzle starts falling apart in a few years. The stickers are pricey, though; sometimes, the stickers are more expensive than the puzzle itself!

I’ll leave you with one last gif(t) before I sign off for the day 🎁

hope to see you soon!! i’m very very excited for the next one 🚃

Mark Rober’s video is perhaps the most famous and successful example in recent memory.

Stuff Made Here’s video goes into a lot more detail about how to build the software behind a puzzle-building robot.

A question for colorblind readers: do you think it’s easier or harder for y’all to distinguish between different shades of the same color?